The rear brakes of all Beetles are drum brakes. The drums are secured to the axle by a large castellated nut torqued to 253 lb ft. This nut should be slackened before the car is raised from the ground. Select first or reverse gear and engage the handbrake, chock the rear wheels, remove the hub caps and the split pin from the

castellated nut. Then slacken off the nut, using a large square T drive (preferably a 'A in. drive), a strong 36 mm socket and a long pipe (the longer the better – a two metre pipe is ideal) to gain the necessary leverage to start the nut. If the nut stays stuck fast and the car moves when you apply pressure, try jacking one side of the car up at a time, removing the roadwheel and chaining a (spare) wheelnut to the chassis. If all else fails, soak the nut in freeing solution or try applying gentle heat to make the nut expand.

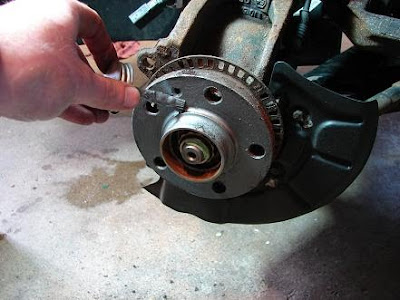

When both axle nuts have been loosened, slacken the rear wheel nuts, engage the steering lock (wheels dead ahead), chock the front wheels, raise the rear of the car and support it on axle stands. Disengage the hand brake. Remove the axle nuts. Slacken off the brake adjusters until the drum turns freely (see Chapter 3). and pull the drums from the splined axle shafts, tapping the drums with a rawhide mallet to centre the shoes or even using a puller if necessary. Some brake shoes contain dangerous asbestos, so don a dust mask and gently wipe the drum and the shoes clean out of doors. If there is less than 0.1 in. of frictional material left on the brake shoes then they will have to be renewed. If a brake drum is scored internally then it should be replaced.

To strip the brakes, use a pair of pliers to remove the shoe retaining springs and their clips. Ease the lower ends of each shoe out from the slot in the adjuster tappet, and then ease the top ends out of the wheel cylinder tappets. Ease out the handbrake cable end and remove the shoe/spring assembly.

Examine the wheel cylinder hoots and brake backplate for signs of brake fluid leakage: if this is suspected, then a wheel cylinder kit, comprising new piston (tappet) seals and boots should be obtained and titled. Clamp off the length of flexible brake hose before removing the wheel cylinder, and bleed the system afterwards. Check that both tappets are free to move and, if they are seized, try using a large screwdriver through the jaws to turn and free them don't force too hard or you will spread the jaws. On really stubborn wheel cylinders which are completely seized the last resort is to remove them from the car, drain all brake fluid from them and then use heat to free the tappets: the heat destroys the tappet seals, which must be renewed. Examine the wheel cylinder bore for damage, and renew if necessary.The hub oil seal can also teak with the result that the brake backplate becomes covered with fluid, but in this case, the fluid will obviously be oil. Because you will normally discover a leaking hub oil seal when you are working on the brakes, a brief description of the necessary work is included here.

Either drain the transaxle of oil, or jack up the side of the car being worked on so that the hub is at a higher level than the transaxle. Unbolt the four hub cover bolts, then pull the cover from the backplate, having placed a suitable receptacle underneath the catch any escaping oil. Remove the old oil seal, the spacer, the '0' rings from the casing and axle, the gaskets either side of the brake backplate, and clean all components. Use a block of wood to drive the new oil seal into position — not forgetting to replace the washer first. Fit the axle '0' ring. spacer and the '0' ring in the cover. Pull the backplate gently forwards until you can gently feed the inner gasket through the hole in the centre of the backplate and into position, fit the front gasket, and carefully reassemble, taking care not to damage either of the gaskets as the bolts are passed back through. Torque the bolts to the recommended level then, with the car back on its wheels or only slightly raised to allow access to the transaxle filler plug on the nearside. top of the transaxle oil.

castellated nut. Then slacken off the nut, using a large square T drive (preferably a 'A in. drive), a strong 36 mm socket and a long pipe (the longer the better – a two metre pipe is ideal) to gain the necessary leverage to start the nut. If the nut stays stuck fast and the car moves when you apply pressure, try jacking one side of the car up at a time, removing the roadwheel and chaining a (spare) wheelnut to the chassis. If all else fails, soak the nut in freeing solution or try applying gentle heat to make the nut expand.

When both axle nuts have been loosened, slacken the rear wheel nuts, engage the steering lock (wheels dead ahead), chock the front wheels, raise the rear of the car and support it on axle stands. Disengage the hand brake. Remove the axle nuts. Slacken off the brake adjusters until the drum turns freely (see Chapter 3). and pull the drums from the splined axle shafts, tapping the drums with a rawhide mallet to centre the shoes or even using a puller if necessary. Some brake shoes contain dangerous asbestos, so don a dust mask and gently wipe the drum and the shoes clean out of doors. If there is less than 0.1 in. of frictional material left on the brake shoes then they will have to be renewed. If a brake drum is scored internally then it should be replaced.

To strip the brakes, use a pair of pliers to remove the shoe retaining springs and their clips. Ease the lower ends of each shoe out from the slot in the adjuster tappet, and then ease the top ends out of the wheel cylinder tappets. Ease out the handbrake cable end and remove the shoe/spring assembly.

Examine the wheel cylinder hoots and brake backplate for signs of brake fluid leakage: if this is suspected, then a wheel cylinder kit, comprising new piston (tappet) seals and boots should be obtained and titled. Clamp off the length of flexible brake hose before removing the wheel cylinder, and bleed the system afterwards. Check that both tappets are free to move and, if they are seized, try using a large screwdriver through the jaws to turn and free them don't force too hard or you will spread the jaws. On really stubborn wheel cylinders which are completely seized the last resort is to remove them from the car, drain all brake fluid from them and then use heat to free the tappets: the heat destroys the tappet seals, which must be renewed. Examine the wheel cylinder bore for damage, and renew if necessary.The hub oil seal can also teak with the result that the brake backplate becomes covered with fluid, but in this case, the fluid will obviously be oil. Because you will normally discover a leaking hub oil seal when you are working on the brakes, a brief description of the necessary work is included here.

Either drain the transaxle of oil, or jack up the side of the car being worked on so that the hub is at a higher level than the transaxle. Unbolt the four hub cover bolts, then pull the cover from the backplate, having placed a suitable receptacle underneath the catch any escaping oil. Remove the old oil seal, the spacer, the '0' rings from the casing and axle, the gaskets either side of the brake backplate, and clean all components. Use a block of wood to drive the new oil seal into position — not forgetting to replace the washer first. Fit the axle '0' ring. spacer and the '0' ring in the cover. Pull the backplate gently forwards until you can gently feed the inner gasket through the hole in the centre of the backplate and into position, fit the front gasket, and carefully reassemble, taking care not to damage either of the gaskets as the bolts are passed back through. Torque the bolts to the recommended level then, with the car back on its wheels or only slightly raised to allow access to the transaxle filler plug on the nearside. top of the transaxle oil.